By Heather Alberro, Associate Lecturer/PhD Candidate in Political Ecology, Nottingham Trent University in The Conversation.

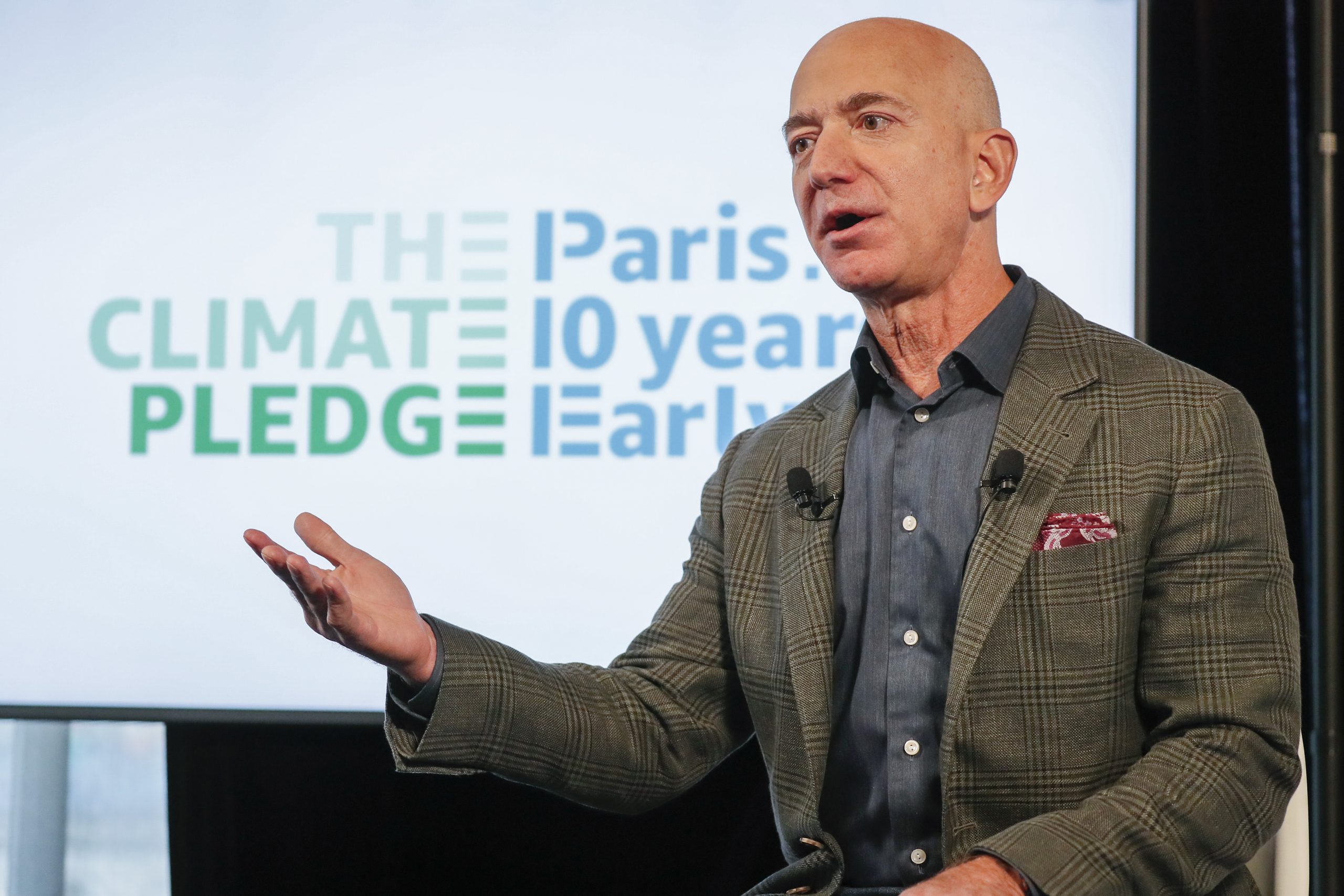

Jeff Bezos, Amazon CEO and the richest man alive, recently made headlines after pledging to donate $10 billion to a new “Bezos Earth Fund” to help combat climate change. It’s one of the largest charitable gifts in history.

Though details regarding the exact kind of work that will be funded are scarce, Bezos noted in his announcement on Instagram that the new global initiative will “fund scientists, activists, NGOs – any effort that offers a real possibility to help preserve and protect the natural world”.

Though Bezos’ interest in climate change is commendable, his latest venture is far more problematic than it might initially appear. Some have already drawn attention to the irony of his decision given Amazon’s enormous carbon footprint and reliance on continuous cheap consumption.

Then there are the numerous controversies surrounding pay and working conditions, notably Bezos’s decision to cut health benefits for part-time workers at his Whole Foods grocery stores, saving the equivalent of what he earns in a few hours.

Bezos’ contribution highlights the dangers of relying on billionaire philanthropy at the expense of the democratic social transformation that is needed to adequately address the climate and ecological crisis. By contributing such significant sums, the wealthy elite exert ever greater influence over the organisations they control, media platforms and public policy discussions.

Perhaps most importantly, billionaires like Bezos represent a failed socioeconomic system that entrenches inequality and exacerbates environmental degradation.

Consolidating power

It is no secret that the world’s wealthy elite – the richest 26 of whom own more wealth than the poorest half of humanity – exert considerable influence over our social and political life.

They use their enormous wealth to mould policies and elections, and even the information we receive via the mainstream media. Jeff Bezos owns the The Washington Post, for instance, while media mogul Rupert Murdoch owns and controls 70% of Australia’s newspaper circulation and several national papers in the UK.

In a similar fashion, the billions in charitable contributions by individuals such as Bezos and Bill Gates allow them control over what organisations like the new “Bezos Earth Fund” do and how they function.

As the American economist Robert Reich points out, it is through such ventures that the rich “convert their private assets into public influence”.

In the fields of political science and sociology, “elite theorists” such as C. Wright Mills have long pointed to the undemocratic implications of wealthy people and business interests wielding disproportionate political power.

Perhaps the most problematic aspect of billionaire philanthropy is that individuals such as Bezos are a key part of the problems they’re seeking to address.

They are the inevitable products of neoliberal capitalism, a socioeconomic system based on endless growth, privatisation of the commons and capital accumulation in increasingly fewer hands.

As I’ve discussed previously, a growing body of evidence points to an association between extreme wealth, inequality and ecological degradation.

The profligate lifestyles of the rich are highly resource and carbon intensive – emissions caused by the lifestyles of the wealthiest 1% of humanity are estimated to be more than 30 times larger than the poorest 50%.

Moreover, research suggests that the more unequal a society, the greater its ecological footprint. This is because the extreme gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots” places pressure on the latter to enhance their social status through increased material consumption.

What can we do? Put a limit on extreme wealth

Billionaires and extreme wealth inequality more generally are inimical to social and ecological well-being. Hence the prominent French economist Thomas Piketty’s recent call to tax billionaires out of existence.

Rather than relying on contributions by the world’s ultra-rich, adopting measures to radically reduce socioeconomic inequality is one place to start.

This can be achieved through progressive tax schemes like that suggested by Piketty and progressive politicians such as Bernie Sanders, or by increasing the minimum wage and introducing a maximum wage. The funds generated could be used to support initiatives such as the Green New Deal.

We cannot rely on the generosity of the world’s wealthy elite, however well-intentioned some may be. The disproportionate amount of wealth and political power they possess – and their profligate consumption of the world’s resources – lie at the heart of our current ecological woes.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Image courtesy of gettyimages.co.uk.